Dynamic hedging is a form of risk management related to derivatives risk. It is the process by which a trader hedges a position in light of shifts in underlying variables, such as delta and gamma.

This is done to avoid losses that could potentially occur if the hedge is not put on.

For example, if a trader sees a stock trading at $95 he could decide he wants to sell a call option with a $100 strike price to help generate income. But this also gives him the obligation to sell the stock (short-sell if he doesn’t already own) if the option lands ITM.

If the stock remains under $100 per share, the trader won’t have to dynamically hedge. If it gets up to that level – or too close for comfort (stocks can move overnight and gap up or down) – he can buy the underlying to cover the option. This would effectively turn it into a covered call.

Traditional payoff diagrams

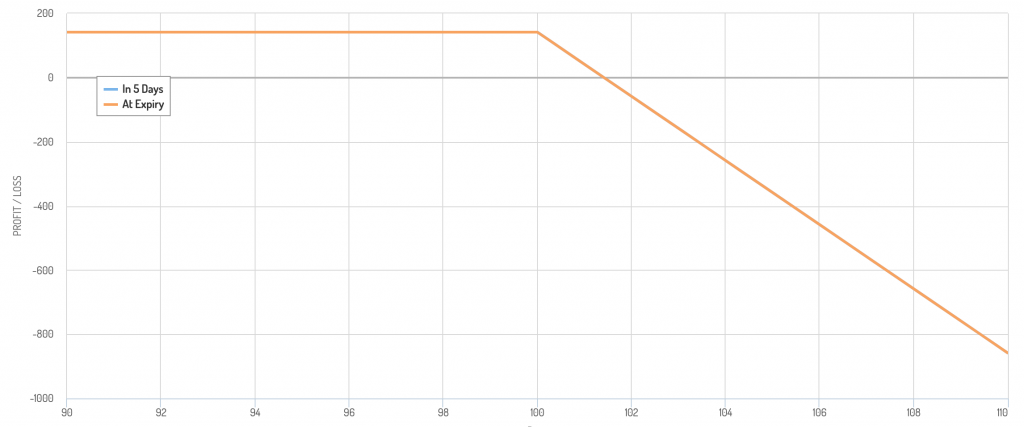

Naked short call

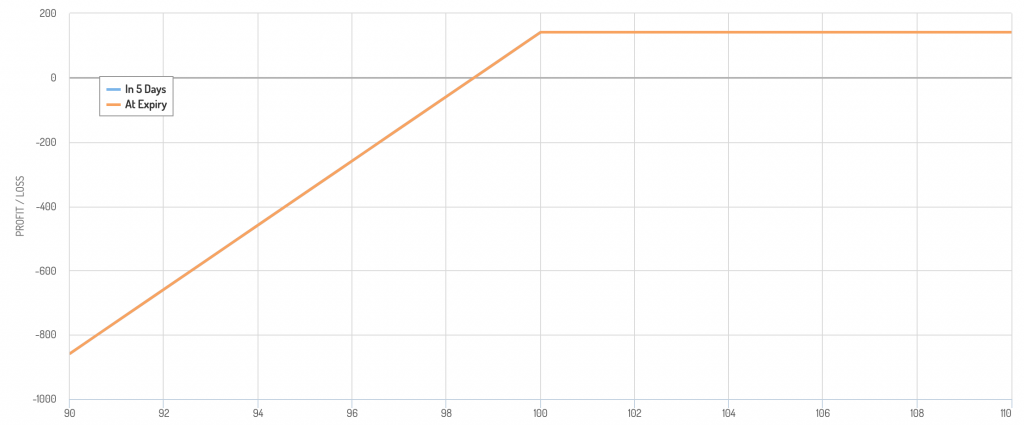

Covered call

Assuming the option finished ITM, the trader would receive the premium as expected without sustaining the losses that would have come with it, if left uncovered.

There are other strategies in which a trader might want to dynamically hedge.

For example, in Options Strategies for Income, we covered the “option wall” strategy.

This is where a trader goes heavier shorting options at a certain price point where, if it were to reach that price level, the trade would be very profitable.

If the trade doesn’t work out, the options expire worthless – the best possible outcome if you’re short them – which helps you generate income or help lower the total amount of any losses sustained if the trade doesn’t pan out.

So, in that sense, it represents a potentially highly convex outcome.

But part of the key to the trade is, if it does work out, you need to dynamically hedge or potentially face losses.

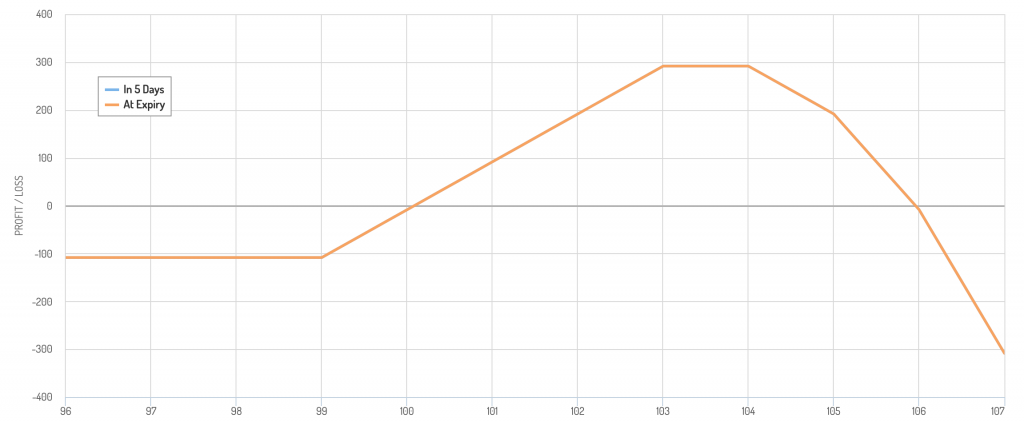

Below is an example of what would happen if:

- Buy 100 shares of a $100 stock

- Buy 1 99-strike put

- Sell 1 103-strike call

- Sell 1 104-strike call

- Sell 1 105-strike call

- Sell 1 106-strike call

One short call would give it a covered call structure. Including the put, it would form a collar (limited P/L range).

Basically, you have a type of modified call spread or modified bull spread.

You could do the opposite to form a modified put spread or modified bear spread (i.e., shorting the underlying, long call, short various puts at different strikes).

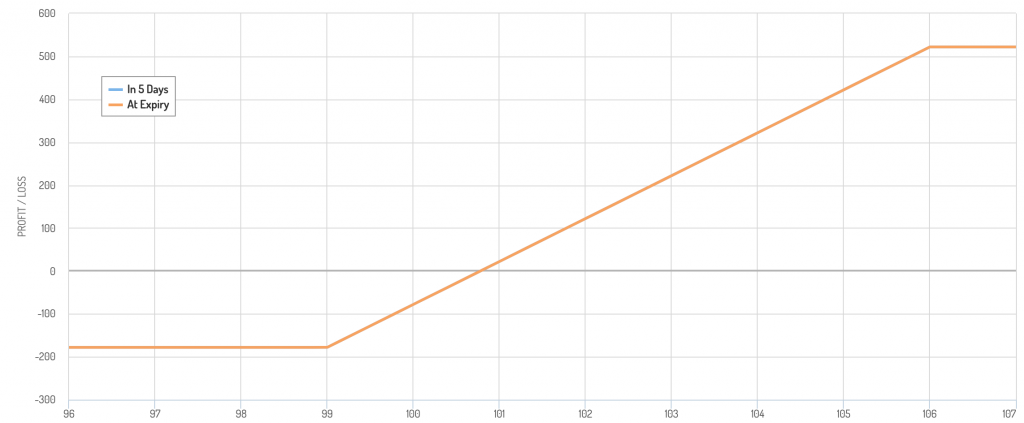

The second short call gives it more of an iron condor look. If price were to get past 104 it would start losing profit. This is the point at which the trader would want to begin dynamically hedging.

The can be called “rebalancing the gamma” as buying the underlying security helps to replicate the original payoff of the option.

To help lock in more profit, he could also buy a 103 put, though this will incur a cost (both the put option premium itself and transactions costs).

If price were to get to 105, the trader could dynamically hedge again. Likewise, buying a 104 put (or another 103 put) would help lock in some profit if price were to reverse.

If price were to get to 106, there would be another dynamic hedge, another long put option, and so on.

Without any dynamic hedging, this is what the payoff diagram would look like with about a 3-to-1 reward-risk trade structure off the bat:

Example trade structure that could require dynamic hedging

A “full” position – a dynamic hedge at each of the secondary short calls, plus a put option bought at the previous call strike – would turn into an elongated collar structure.

Options trading strategies that have a lot of convexity to them, especially with spread-related strategies, may need to involve some type of dynamic hedging since overweighting the short side may be the reason why they achieve that convexity to begin with.

Markets for dynamic hedging

Some markets have limited hours, which doesn’t make them ideal fits for trades that could require dynamic hedging.

Stock markets are officially open for only 6-7 hours in many markets. Unofficially they are open for up to 16 hours per day Monday through Friday (excluding holidays) in the US when taking into account pre-market and post-market trading hours. But not all traders have access, and the liquidity is lower during unofficial market hours (sometimes significantly so).

Because stocks and ETFs have gaps due to the non-continuous nature of these markets, dynamic hedging strategies don’t always work perfectly.

Some traders may feel more comfortable using them in futures markets or currency markets that are open 24/5.

This includes spot and futures FX markets, most commodity markets, stock index futures, and bond futures.

Not all markets have underlying options markets – or options markets that are sufficiently liquid enough.

Conclusion

Dynamic hedging involves hedging derivatives risk and represents one component of risk management.

The examples of dynamic hedging in this post relate to basic delta and gamma hedging – the most common and basic forms of hedging – and are designed to give a brief overview.

Dynamic hedging can be much more complicated in practice depending on a trader’s goals. The greater the number of variables that move around – e.g., volatility, interest rates, second- and third-order “Greeks” – the more complex the dynamic hedging process is. That, in turn, can create more transaction costs.

There are many variables that are not stable that bring risk into a trade and an overall portfolio. If there are correlations among the variables that can bring in additional complexities.